The AI overlords have already won

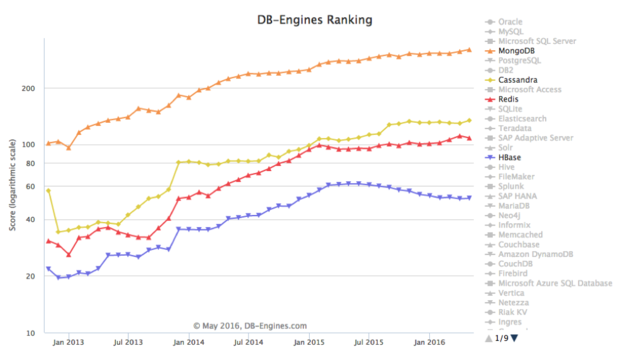

AI and its many subsets, including machine learning and bots, have been incredibly hyped of late, claiming to revolutionize the way humans interact with machines. InfoWorld, for example, has reviewed the machine learning APIs offered by the major clouds. Everyone wonders who will be the big winner in this new world.

Bad new for those who like drama: The war may already be over. If AI is only as good as the algorithms — and more important, the data fed to them — who can hope to compete with Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft, all of which continually feast on the data we happily give them every day?

All your bots are belong to us

Former Evernote CEO and current venture capitalist Phil Libin has suggested that bots are on par with browsers 20 years ago: basic command lines control them with minimalistic interfaces. (“Alexa, what is the weather today?”) Bots, however, promise to be far richer than browsers, with fewer limits on how we inject data into the systems and better ways to pull data-rich experiences therefrom — that is, if we can train them with enough quality data.

This isn’t a problem for the fortunate few: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and a handful of others are swimming in data. In exchange for free services like email or Siri, we gladly give mountains of data to these companies. In so doing, we may be unwittingly building out competitive differentiation for them that could last for a long, long time.

Who, for example, can hope to compete with Google’s sense of location, given its mapping service, which relies on heavily structured data that we feed it every time we ask for directions? Or how about Facebook, which understands unstructured interactions between people better than anyone else?

All trends point to this getting worse (or better, depending on your trust of concentrations of power). Take your smartphone. Originally we exulted in the sea of apps available in the various app stores, unlocking a cornucopia of services. A few years into the app revolution, however, and the vast majority of the apps that consume up to 90 percent of our mobile hours are owned by a handful of companies: Facebook and Google, predominantly. All that data we generate on our devices? Owned by very few companies.

On the back end, these same companies dominate, making up the “megacloud” elite. Tim O’Reilly first pointed out this trend, arguing that megaclouds like Facebook and Microsoft would be difficult to beat because of the economies of scale that make them stronger even as they grow bigger. While he was talking about infrastructure, the same principle applies to data. The rich get richer.

In the case of AI bot interfaces, the data-rich may end up as the only ones capable of delivering experiences that consumers find credible and useful.

CompuServe 3.0

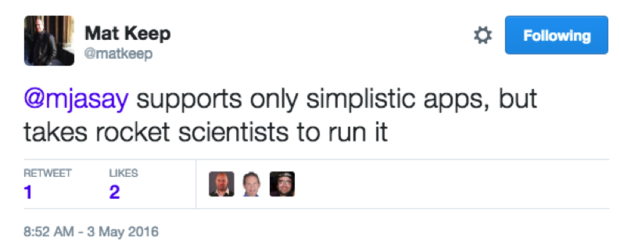

If this seems bleak, it’s because it is. It’s hard to see how any upstart challenger can hope to rend control of consumer data from these megaclouds with the processing power, data science smarts, and treasure trove of user info. The one ray of light, perhaps, is if someone can introduce a superior “curation layer.”

For example, today I might conversationally ask Apple’s Siri or Amazon’s Alexa to point out nearby sushi restaurants. Both are able to tap into a places-of-interest database and spit out an acceptable response. However, what if I really want not merely nearby sushi restaurants, but nearby sushi restaurants recommended by someone whose food preferences I trust?

Facebook appears to be in pole position to use its knowledge of my human interactions to give the best answer, but it actually doesn’t. Just because I’m friends with someone on Facebook doesn’t mean I care about their preferred restaurants. I almost certainly will never have expressed my belief in digital text that their taste in food is terrible. (I don’t want to be rude, after all.) Thus, the field is open to figure out which sources I do trust, then curate accordingly.

This is partly a matter of data, but ultimately it’s a matter of superior algorithms coupled with better interpretation of signals that inform those algorithms. Yes, Google or Facebook might be first to develop such algorithms and interpret the signals, but in the area of data curation there’s still room for hope that new entrants can win.

Otherwise, all our data belongs to these megaclouds for the next 10 years, as it has for the last 10 years. And they’re using it to get smarter all the time.

Source: InfoWorld Big Data